AANHPI Disability and Neurodivergent Narratives

Welcome to AMBIV Collective's gallery celebrating the intersectionality of disability, neurodivergence, and Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) cultural heritage through empowering narratives that shatter stereotypes and illuminate the richness of our diverse human tapestry.

ABOUT

Launched in May 2024, this virtual gallery celebrates the tenacity, strength, and unwavering spirit of the disabled and neurodivergent AANHPI communities.AMBIV Collective invited this community to share their stories, amplifying narratives that shattered stereotypes. Participation was a call to action championing diversity, fostering acceptance, and empowering a more inclusive future.This gallery is here to challenge stereotypes and misconceptions, paving the way for greater acceptance and inclusivity. Sharing narratives and artwork holds remarkable power in battling stigma, increasing representation, and ultimately uniting diverse communities. Sharing lived experiences offers a sense of connection and validation to those who feel isolated, breaking down barriers of stigma and providing a lifeline of understanding and empathy. These narratives inspire hope, foster solidarity, and remind others that they are not alone, creating a community of support and empowerment where every voice is heard and valued.

Although this gallery has launched, we will continuously welcome and embrace new written narratives, visual artworks, and audio pieces from the community to further amplify voices, foster growth, and strengthen the bonds that unite us. Please let us know via guestbook or directly reaching out to AMBIV Collective.

WHY THIS MATTERS

For too long, the narratives of disabled and neurodivergent AANHPI individuals have been marginalized, their unique experiences overshadowed by societal biases and misconceptions. By creating a space to share their stories, we not only celebrate the richness of their identities but also foster a deeper understanding and appreciation for the intersectionality of disability, neurodivergence, and cultural heritage. For some, resilience against adversity was not a choice but a necessity for survival and thriving.

CONTENT WARNINGS

While some pieces may touch upon sensitive topics or contain content that could be triggering, we believe in providing a space for authentic expression. To ensure a mindful and respectful experience, we will thoughtfully place content advisories before submissions that may benefit from additional context or viewer discretion.

AMBIV Collective

AMBIV Collective is a social impact agency empowering disability and neurodivergent communities with research-powered support and community-led solutions.We empower disability and neurodivergent communities by uplifting individuals and connecting the community through events, fostering a vibrant network. We strive to build community-led solutions fueled by ongoing research, ensuring our initiatives are rooted in the diverse needs and aspirations of the individuals we serve. We aim to cultivate an inclusive, collaborative, and informed ecosystem that embraces diversity, innovation, and shared knowledge, fostering a dynamic space for growth and mutual support.

Note from the Curator, Kim Chua

I am honored to present a powerful collection amplifying the multifaceted narratives of disabled and neurodivergent individuals from the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) communities. This act celebrates the rich intersectionality of their experiences, igniting a resurgence of energy and vulnerability as we boldly embark on a new era of strength, courage, and radical acceptance.By courageously sharing their narratives, our contributors offer a profound sense of connection and validation to those navigating the complexities of intersecting marginalized identities. Their stories provide a lifeline of empathy and understanding, breaking down barriers of stigma, isolation, and discrimination.I invite you to join us on this transformative journey. Whether you resonate with these intersections or are an ally seeking greater awareness, immerse yourself in these narratives through captivating stories and thought-provoking artwork. Be open to having your perspectives challenged and your compassion expanded. Together, we can pave the way for future generations to embrace their authentic, multidimensional selves unapologetically.I thank you for taking the time to explore, listen, and learn from what our contributors have courageously and thoughtfully shared. Their narratives hold the power to unite diverse communities through understanding, acceptance, and solidarity.— Kim Chua, Co-Founder of AMBIV Collective

The Capacity to Dream

Celina Tupou-Fulivai (Artwork — 2024)

Page 36 of "Hear See Here Zine 2024"

Dennis Tran (Art — 2024)

ADHD: Asian Diary of Hyperactivity Days

Jean Munson (Artwork — 2024)

Book Display

Martin Tran (Photo & Book Display — 2024)

Page 38 of "Hear See Here Zine 2024"

Niko Galindez (Art — 2024)

Artwork

Pam Maranan Parker (Art — 2024)

What It Means to be Disabled AANHPI

Ellen Kim (Text Interview — 2024)

Inclusivity in Japanese Special Education: A Comparative Analysis

Ellen Kim (Research Paper — 2024)

Reflection by Irene Nham

Irene Nham (Text — 2024)

Embracing My Journey: Strength Through Adversity and Community

Khris Baizen (Text — 2024)

Coursing Through the Haze: Navigating Disability and Neurodivergence as an AANHPI Woman

Kim Chua (Text — 2024)

Invisible by Disability, but Visible in Community

Kristen Higa (Text — 2024)

Reflection by Lilian Nelson

Lilian Nelson (Text — 2024)

Reflection by Maddy Ullman

Maddy Ullman (Text — 2024)

Neurodivergent Asian American

Nathan Chung (Text — 2024)

Finding My Tribe: A Neurodivergent AANHPI Woman's Journey

Rachel Cometa Estuar (Text — 2024)

Reflection by Selena Moon

Selena Moon (Text — 2024)

[CONTENT WARNING]

Reflection by Sydney Rae Chin

Sydney Rae Chin (Text — 2024)

[CONTENT WARNING]

You Call Me Corona

Amy Manion (Spoken Word Video — 2024)

Reflection as a Neurodivergent Lao and Vietnamese Asian American

Sarina Tran-Herman (Video — 2024)

GALLERY OF NARRATIVES

To the courageous artists who have contributed their narratives and works, your strength in the face of adversity is an inspiration. We are deeply grateful for your vulnerability in sharing your stories, which have shattered stereotypes and fostered a more inclusive world.Alphabetically sorted by first name.

Amy Manion

[Content Warning] You Call Me Corona

(Spoken Word Video — 2021)

Celina Tupou-Fulivai

The Capacity to Dream

(Art — 2024)

Dennis Tran

Page 36 of "Hear See Here Zine 2024"

(Art — 2024)

Ellen Kim

Cure Ableism

(Art — 2024)What It Means to be Disabled AANHPI

(Interview — 2024)Inclusivity in Japanese Special Education: A Comparative Analysis

(Research Paper — 2024)

Irene Nham

Writing

(Text — 2024)

Jean Munson

ADHD: Asian Diary of Hyperactivity Days

(Art — 2024)

Khris Baizen

Embracing My Journey: Strength Through Adversity and Community

(Text — 2024)

Kim Chua

Coursing Through the Haze: Navigating Disability and Neurodivergence as an AANHPI Woman

(Text — 2024)

Kristen Higa

Invisible by Disability, but Visible in Community

(Text — 2024)

Lilian Nelson

Writing

(Text — 2024)

Maddy Ullman

Writing

(Text — 2024)

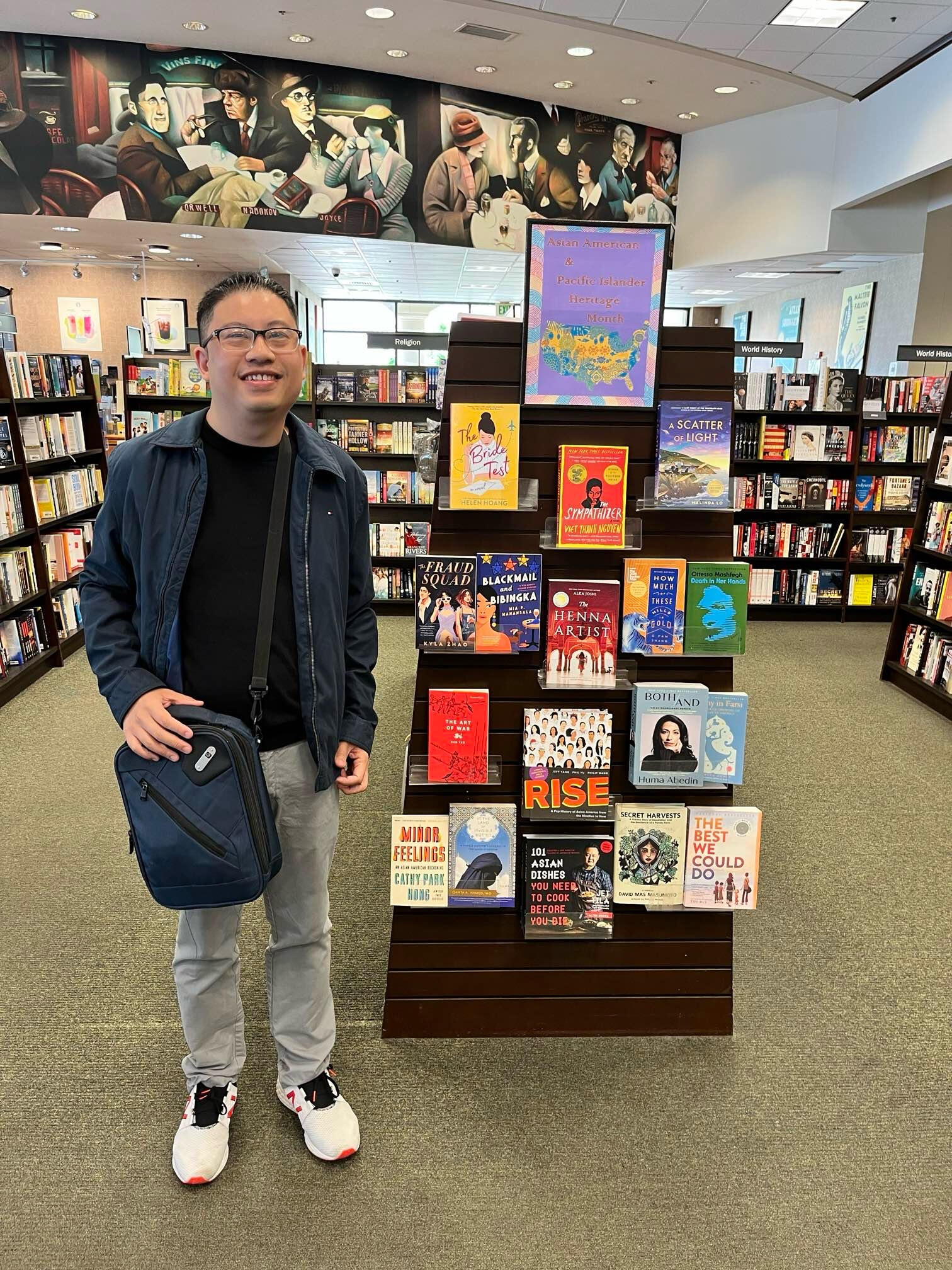

Martin Tran

Book Display

(Photo — 2024)

Nathan Chung

Neurodivergent Asian American

(Text — 2024)

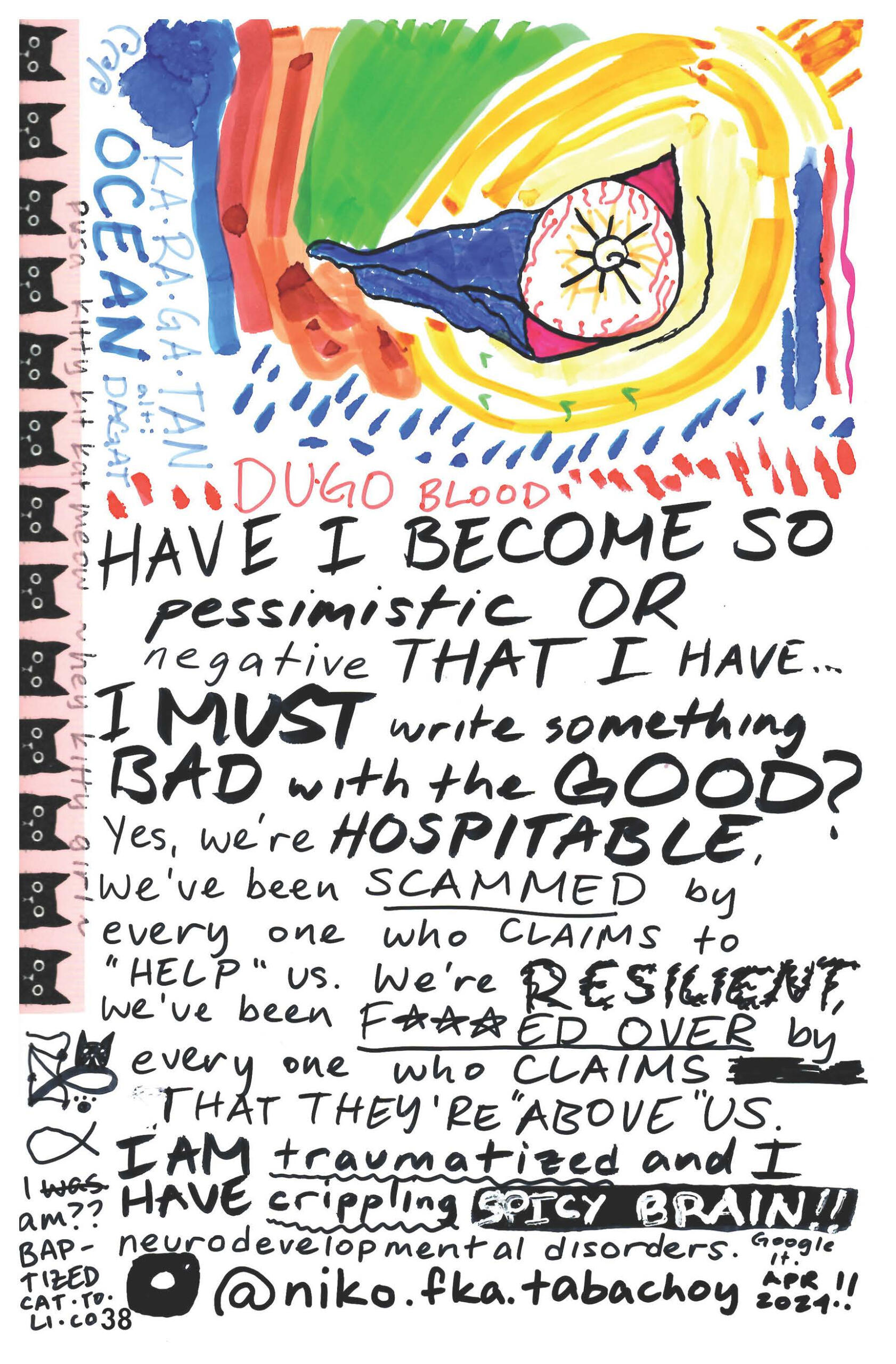

Niko Galindez

Page 38 of "Hear See Here Zine 2024"

(Art — 2024)

Pam Maranan Parker

Artwork

(Art — 2024)

Rachel Cometa Estuar

Finding My Tribe: A Neurodivergent AANHPI Woman's Journey

(Text — 2024)

Sarina Tran-Herman

Video

(Video — 2024)

Selena Moon

Writing

(Text — 2024)

Sydney Rae Chin

[Content Warning] Writing

(Text — 2024)

Amy Manion

Amy Manion is a biracial East Asian woman with brown eyes, a long face, tall, sturdy build, long brown, graying hair in her late 30s and has a light complexion with olive undertones.

You Call Me Corona

Created Fall 2021, Submitted May 2024 — Spoken Word Video by Amy Manion

[Content Warning: su*cide mention]

Video is of Amy Manion, a biracial East Asian woman, wearing a bright red and gold patterned traditional Chinese silk jacket.

Transcript

“You call me Corona.”

September 2020.Traditional Chinese bright red silk jacket. My aunt gave it to me. It may be from one of our ancestors. I walked down the street with it on. I can't hide these eyes, so I wear a token of them on my body because it doesn't matter what I wear. You think I am Corona? I saw it in the way you looked at me when I was walking down the street. My height from my irish dad. That can't fool you anymore. Make you do a double take because tallness and light skin equals american to you. And yet another, you cross the street to avoid me and not others up ahead.Imagine me running up after you to call you out on it. It's hard to yell out at racial violence when you're struggling to breathe. But I did it anyway because you needed to know. Because nothing you can say can change the way you made me feel.And you, yet another, you who chose to single me out in the Harvard yard on March 13, 2020, you who looked at me in outrage are in disgust. Don't bother, because I will keep walking down the street in my traditional chinese bright red silk jacket. My aunt gave it to me. This

may be for one of our ancestors.This is dedicated to those in the asian diaspora who have lost their lives due to suicide. Racism kills. It almost killed me when I tried to take my own life.Translated by Yi Yang Yuan Shane un petit frere.

Amy Manion is a low income, psychiatrically disabled, biracial Asian woman of faith living on Turtle Island, born in what is now called Boston, Massachusetts. In the following spoken word video, originally created around the Spring/Summer time of 2020, Amy talks about her experiences walking down the street with East Asian features around the advent of COVID-19 widespread fears. Although it is a few years removed from that time, Amy struggled with agoraphobia and social anxiety and fears of being judged for her race even before 2020. She has found it challenging to grapple with her place in society while striving to live an authentic, embodied, meaningful and free life with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder with psychotic features and as a trauma survivor.The original version of this piece first appeared in the online collection of the Neurodivergence Gallery in 2020. An edited version appeared as a part of an artist series during the Fall of 2020 for the Massachusetts Coalition for Suicide Prevention. Shortly after, Amy had the privilege of having her work translated into Chinese characters by UMass Chan Medical School’s student-led organization Project Harmonious whose aim was to outreach to and bring awareness of the mental health experiences of the Chinese population in Massachusetts. This version was featured during the Fall 2021 virtual “This is My Brave: Stories from the APIDA Community” show.Amy believes that stories heal and she feels it is her responsibility to be a witness to her experience and tell stories for her own healing and well-being and life. She hopes other people of the Asian diaspora will feel less alone and feel empowered to tell their stories. Amy currently tells stories through song and spoken and written words. She has a love for comedy and life and loves acting and improv and standup comedy, all of which she has taken classes in. She studied Expressive Arts Therapy at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Celina Tupou-Fulivai

The Capacity to Dream

May 2024 — Artwork by Celina Tupou-Fulivai

Image is a digital painting of a young girl with brown skin and black curly hair sleeping, wearing a white shirt with gray and red stripes. The text reads "The Capacity to Dream."

Digital painting of my daughter Zola based on the quote by Kathleen Seidel, "Autism is as much a part of humanity as is the capacity to dream."

Dennis Tran

Page 38 of "Hear See Here Zine 2024"

May 2024 — Artwork by Dennis Tran

Image is a handmade zine/ picture and photo collage from Dennis Tran featuring stickers that read "Slow & Steady," "Light," "Make it a Habit," "Goals," "Do Your Best!", "it's about listening to your heart and being brave enough to go where it takes you; also: always carry an extra apple!" and "a little boy and his grandpa's journey to make a new land their home." There are stickers of ramen and a bento box as well as the book cover of "The Space Between Here & Now" by Sarah Suk.

Ellen Kim

Ellen Kim is a third generation Korean American female with neurodivergence.

Contents

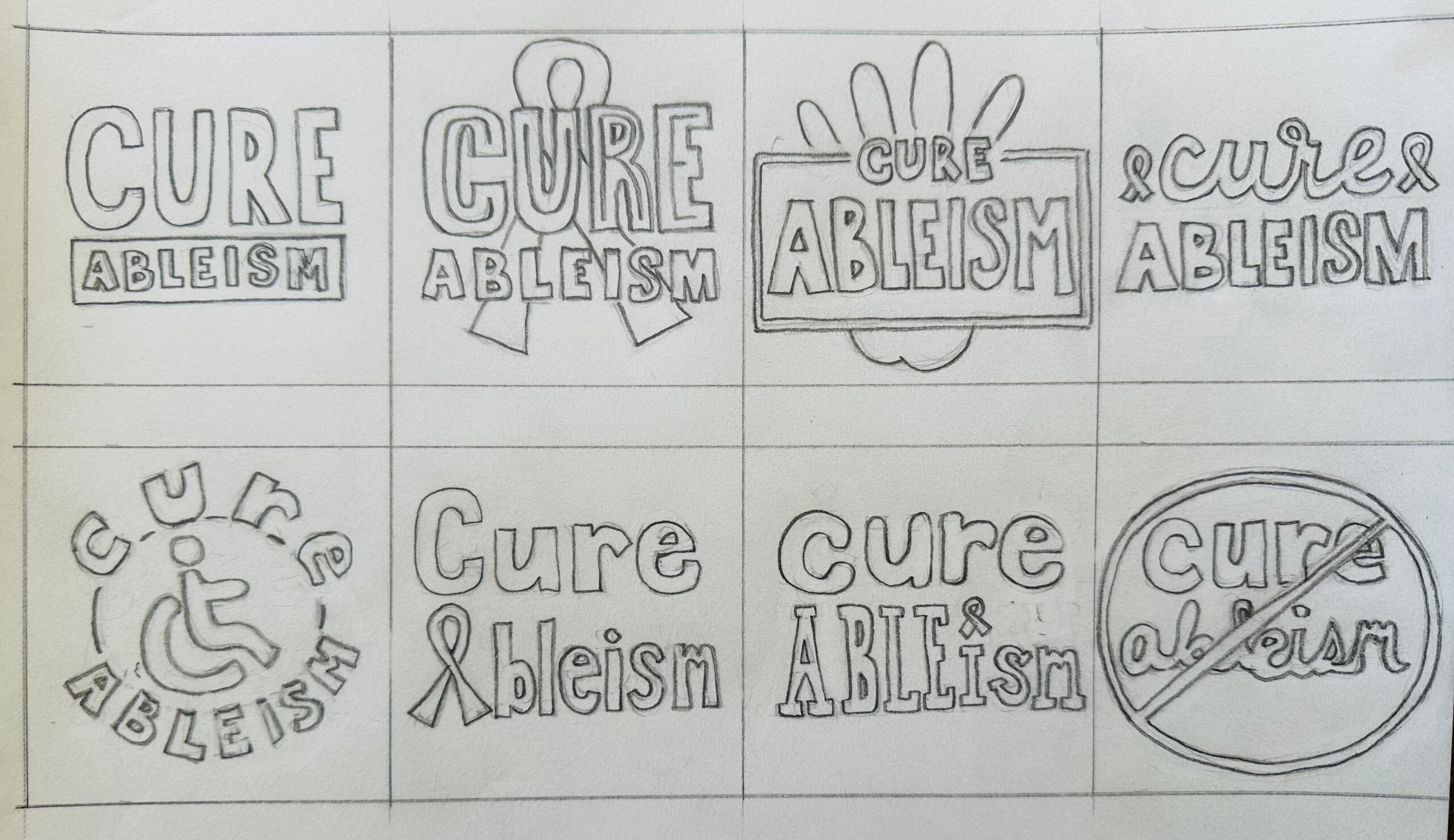

01. Cure Ableism

02. Sketches of "Cure Ableism"

03. What It Means to be Disabled AANHPI

04. Inclusivity in Japanese Special Education: A Comparative Analysis

Cure Ableism

May 2024 — Artwork by Ellen Kim

Image is a digitally designed circle logo of "Cure Ableism" by Ellen Kim. The circle has a thick black border with a light purple-maroon background, at the center is a white awareness ribbon. The ribbon itself is a flat, curved piece of material that is wider in the middle and tapers towards the two ends that meet to form the loop. The overall shape resembles a stylized letter "Q" rotated sideways. "Cure Ableism" is shown in dark text above the ribbon.

The disability statistics are staggering. Approximately 26% of the U.S. population has a disability, representing the largest minority group in America and cutting across all demographic and ethnic groups. In general, these disabilities lead to limited access to education, lower wealth, restricted access to health services, and discrimination.Ableism, also known as disability injustice, is defined as the system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on socially constructed ideals of desirability, normality, and productivity. Simply put, Albeism is discrimination towards those with disabilities. Unfortunately, many of the injustices are due to perpetuated systemic reasons. With a social and economic system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on manmade constructs, ableism attempts to divide people in our society as “able people” who are deemed as normal, productive, and contributors to our society and “disabled people” who are considered lazy, deviant, undesirable, and unproductive. This unfairly opens the perspective that people with disabilities need to be fixed to become normal rather than ideals of inclusion as they are and who they are.Although there has been major legislative progress, like the Federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, it’s our society’s general viewpoint of people with disabilities that requires substantive change. This is the primary reason I aspire to be an animator who creates uplifting visual and authentic stories highlighting people with disabilities. I hope to counter ableism and positively portray those with disabilities in mainstream media and build greater empathy and lower discrimination by non-disabled people. I chose the phrase “Cure Ableism” because it highlights that the core problem isn’t how best to cure people with disabilities towards what society calls normal but rather to cure society’s unjust discrimination against people with disabilities.

Sketches of "Ableism"

May 2024 — Artwork by Ellen Kim

Pencil sketches of variations for "Cure Ableism" by Ellen Kim. Sketches include "Ableism" outlined in a box, a hand figure behind a box labeled as "Cure Ableism", awareness ribbons on the left and right side of "cure", the disability symbol of a figure on a wheelchair, and a circle with a diagonal line drawn over "cure ableism."

Here are a few logo sketches on ableism that I am currently working on for one of my graphic design courses at a local community college. I really like the concept of "cure ableism" because I think that many people tend to think that people with disabilities need to be cured in order to be normal when many people need to be cured in the way that they are viewing those with disabilities.

What It Means to be Disabled AANHPI

May 2024 — Interview with Ellen Kim

What’s the first thought that comes to mind when it comes to the intersectionality of being a disabled AANHPI?

My first thought concerning the intersectionality of disability, AANHPI, and female is a general misunderstanding, misperception of capabilities, and sometimes unempathetic exclusion and acts of intentional or unintentional ableism. Also, I think there is an unspoken element of embarrassment or shame that AANHPI disablement carries within one’s family and one’s AANHPI ethnic or social groups.In your experience, how does your identity as a disabled AANHPI shape your perspective?

From an early age, I knew that I was different from others. I thought and acted differently relative to most of my classmates and teachers. Over the years, I have started to view my disability as an asset rather than a deficit. It has helped me see the world differently, allowing me to solve problems uniquely and bring something new to groups. My perspectives now are more empathetic towards others, observing how one acts given their context and circumstances. I’m more understanding of what authentic inclusion looks and can feel like. This is why I am keenly interested in disability studies and strive to make an impact now and in the future.Can you share how being both disabled and AANHPI influences your sense of self?

Candidly, my identity as a disabled AANHPI was initially shaped by how others viewed and characterized me. I knew I was different, so I assumed those around me, like teachers and other students, knew where I fit. I tried to stay within the box where society had placed me. As I grew older, I realized I have agency and control of my identity, shaped by my unique blend of heritage, passions, experiences, and how I want to make my mark in this world. The initial community that I gravitated towards was manga/anime. This grew into a strong passion for Japanese culture and art practices like Kintsugi, a fine art form of pottery reparation that considers one’s frailties as one's unique beauty. I view myself as a human kintsugi.Can you describe the significance of being a disabled AANHPI in shaping your experiences and aspirations?

Being a disabled AANHPI has taught me that society, in general, likes to categorize people to make life and relationships simple. It is easier to see black and white than millions of shades of gray. Therefore, most people don’t know what people with disabilities go through daily at school or in their activities and how their challenges shape or alter their experiences. But as I grew older, I realized I could adapt to this world without overly sacrificing who I am and want to be. Admittedly, I’m still working on this. But it’s through this newfound sense of agency, I want to show the world what I am capable of. I discovered my career aspiration to be an animator who creates uplifting visual and authentic stories highlighting people with disabilities. I hope to counter ableism and positively portray those with disabilities in mainstream media.What aspects of being a disabled AANHPI do you find most empowering or challenging?

Overcoming social labels and their connotations is the most challenging, but at the same time, it will be the most empowering as well. People view a person differently when they are made aware of her disabilities. They typically have fewer expectations from you or don’t think you are as capable as others. It’s frustrating. I believe this is why many hide their disabilities. What I find the most empowering about my disability is that I think differently than many of my peers. I solve problems differently with resilience. I see exciting connections that many don’t see. I view with extreme detail the things that most don’t see. I genuinely believe that everyone has a superpower. I think my superpower is a direct result of my disability. It’s the ability to create short stories (in my mind) that connect different themes in unique and creative ways but are still grounded in realism and authenticity.How do cultural values and beliefs influence your understanding of disability as an AANHPI individual?

As a third-generation Korean American, I’m unsure whether my ancestry or ethnic culture has materially and directly influenced me thus far, although I cherish my family’s customs and traditions. I know that there is a high expectation, primarily academic, that the AANHPI community has on its younger generations so that they can live “a better life” than their parents.

Interestingly, I may be more influenced by Japanese cultural values than Korea’s. I’m taking a Japanese history course at Stanford University, studying the differences between Japanese and American elementary education. The Japanese model focuses on the development of the “whole” body (mind, heart, health, etc.) in contrast to the U.S. model, which tends to focus mainly on the intellectual development of the mind. Consequently, a Japanese student with a disability is considered equal to those without disabilities on day 1 of their educational experience. In contrast, a student with disabilities in the U.S. is often segregated from non-disabled people in some material way, which I think perpetuates a lack of understanding and empathy by all students.What unique insights or perspectives do you bring to discussions about disability as an AANHPI person?

As a high school student, I don’t have a wealth of life experiences thus far. Still, I do understand the struggles of overcoming one’s challenges caused by disability and a growing sense of society’s viewpoints and reactions in the K12 educational environment. This is why I want to focus much of my attention on disability studies and animations that highlight those with disabilities, how it feels to be victimized or discriminated - even in the slightest way, yet also create an uplifting and meaningful experience for everyone.

Inclusivity in Japanese Special Education: A Comparative Analysis

June 2024 — Research Paper by Ellen Kim

Background and IntroductionPeople with disability are the largest minority group in the world. In 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that roughly 1.3 billion people are living with disability; that is almost 16% of the world’s population. In Japan, there are approximately 9.6 million people with disabilities, representing 7.6% of the total Japanese population based on a 2018 Annual Health report produced by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

UNICEF estimated that children comprise a meaningful portion of the global population, with nearly 240 million children impacted in 2022. Given the significant number of students with disabilities worldwide, the need for inclusive education transcends borders. The challenges in building an inclusive education system, from costs to support, are not unique to any one country. These are global issues that deserve our collective attention.For many years, the Japanese education system has outperformed many of its global counterparts in Science and Math, prompting other nations, including the United States, to better understand the key drivers of the Japanese system. In Japan, “95 percent of all junior high-school students go on to attend high school; in 2011, 96 percent of high-school students graduated, and nearly three-quarters went on to some kind of post-secondary education” (Hirata 204). These were staggering numbers; yet they are misleading. High matriculation rates fail to account for the experience of students with disabilities and their families. In fact, “nearly 90% of people in Japan believe discrimination and prejudice against those with disabilities continues to persist” (Kayama and Haight 28). More generally, in many East Asian cultures, there is a stigma attached to having a child with a disability: “Within some Asian cultures, the birth of a child with a disability is believed to signify the family’s wrongdoing” (Bogart). This culture of disability further exacerbates the challenges faced by students in Japan.Today, the special education model in Japan follows that of the United States but at a much slower pace. This is especially true regarding self-determination and inclusive classrooms: “Japanese public schools began implementing formal special education services for developmental disabilities in the 2007-2008 school year, decades after the United States implemented the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, in 1975” (Kayama and Haight 25). However, overcoming specific institutional systems such as segregated schools, standardized instruction, and educational hierarchy may prove challenging in Japan’s adoption of inclusive classrooms in the near future. These issues may be tied to a historical need for greater human productivity based on topological limitations and deeply held ideals of harmony, interdependence, and collectivism within larger groups. For example, the hierarchical structure of feudalism in Japan, which prioritized loyalty and collective work, may have influenced the current educational hierarchy that hampers the inclusion of students with disabilities. In other words, disrupting harmony in the classroom by accounting for the needs of students with disabilities may not be preferable for school administrators, educators, non-disabled students, and their parents.This paper explores the historical contexts of the disability culture in Japan and traces the complex evolution of disability politics, including special education, during the late twentieth century. Taking a comparative approach, this paper strives to explain how and why special education today looks differently in Japan than in the United States, specifically focusing on inclusivity. The paper argues that Japan should look to the United States for a more inclusive approach to special education, creating less restrictive environments and more individualized educational paths. In the United States, for instance, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) ensures that all children with disabilities have access to a free and appropriate public education that meets their unique needs. This law has been instrumental in promoting inclusive education practices and could serve as a model for Japan.

Irene Nham

May 2024 — Writing by Irene Nham

A photo of Irene Nham, her husband, and son smiling together in the moment as they're having fun with a backdrop of forest park at sunset.

Before our baby turned one, I already had an inkling, call it mother's intuition or spidey sense, there was a reason for my child's developmental delays. We were constantly reassured that delays in boys were fairly common, especially given the challenges of the pandemic, but it was hard not to compare. EVERYONE would tell us that it was normal for boys to be behind, that every child develops at their own speed, and that our child would eventually catch up.We wasted no time and promptly sought support from our pediatrician who referred us to the Regional Center for Early Intervention. It was a steep learning curve trying to understand and navigate the resources.Autism growing up was non communicado, it was a blessing that I worked in the healthcare field and was surrounded by people who were knowledgeable about the resources. They helped coach us on questions to ask our Regional Center service coordinators. Aware that the timeline for an official Autism diagnosis by age 3 was uncertain, we were proactive and arranged for a psychological evaluation covered by our insurance two months before our child's third birthday. We were informed that having an official diagnosis would provide us with accessibility and continuity to more services before our transition to the Lanterman unit.Once Autism became an official diagnosis for us it opened up a never ending list of questions. One of the burning questions was, how do we tell and educate our Vietnamese immigrant parents, whose limited education, language barriers, and not being technologically proficient posed a challenge? English was not their first language or even their second or third! How would we educate them on Autism when the literal translation from English to Vietnamese doesn't even convey an accurate explanation or description? Searching for resources in Vietnamese proved difficult. Videos either had English dialogue with Vietnamese subtitles, inaccessible for my mother who is also visually impaired OR the videos dialogue was in Vietnamese, leaving us unsure of their accuracy or type of information being spoken about. Vietnamese is not our primary home language, my family speak Cantonese and my husband's side is TeoChew.The world of parents with kids with special needs is already challenging enough, but educating our support systems on how to best support and communicate with their grandchild is another layer of complexity.

Jean Munson

Jean Munson is a Filipina American with ADHD.

ADHD: Asian Diary of Hyperactivity Days

May 2024 — Artwork/ Zine by Jean Munson

Click here to access Jean's zine as a PDF.

IMAGE DESCRIPTIONS

Page 1: at the center is a photo of Jean Munson, a Filipina American with long black hair wearing maroon-rimmed glasses and a dark blue denim jacket, smiling at the camera as she decorates an art piece with chalk. The text reads "2024" "ADHD: Asian Diary of Hyperactivity Days by Jean Munson." There are orange and teal squiggly waves at the bottom right corner. At the top left corner is a digital design of a yellow, red, and teal paper fortune teller. A paper fortune teller is a hand-folded origami toy made from a patterned square sheet of paper, with four protruding petals that open and close to reveal hidden written fortunes inside when manipulated through the motions of an interactive folding game.Page 2: Titled "Quiet, Obedient Child" - the text reads: "When I look back on my life, I understand there are signs of my ADHD that were very apparent that I lacked knowledge on its abilities and hindrances. I started my kindergarten year wrecking the classroom and spent a number of days in time out. I don’t know how I got there. I craved excitement. At home, I was a quiet, obedient child who slept in the afternoons under her dad’s armpits on the floor and ate sardines out of a can for lunch. I was easy to please as long as it entailed watching my brother play video games as he was hyper fixated or reading books til my arms grew heavy. But a structured classroom drove me to a deep need for stimulation because I was bored." The page features a young Jean smiling with her eyes closed at the camera, it's a vintage photo with her wearing a striped black and white dress, black hair tied up into a ponytail with fringe. At the top are decor: purple sparkle and yellow and red school desk attached to a chair.Page 3: Titled "The Death of Me" - the text reads: "By the time I got to first grade I would become the good little kid who always did her homework but still bombed tests. My behavior improved at this age because of the amount of storytelling role playing, field trips, and art projects that were embedded into the curriculum. I began to thrive with stimulation that enhanced the lesson beyond a transaction. Homework and perfect attendance became areas of my

academic life that I focused on to perfect and get by because testing was the death of me. The quiet, the rising anxiety, and long hours of sitting drove me to look within and find incompetency. Suddenly my memory was wiped of all the things I could comprehend since my mom gave me her mask of memorization. With memorization, nothing would stick or impact me as a valuable lesson. I would toss it every quarter and new school year." At the center features a vintage photo of a young Jean with short black hair, wearing a green headband, smiling happily as she poses with one arm arched to her side and the other arm holding a white bunny rabbit plush. The page is decorated with digital stickers: a yellow happy face, a purple squiggly line, a red band of yellow happy faces and yellow lightning bolts, as well as a Tele-Viewer. A Tele-Viewer is a pair of binoculars-like viewers that contain a rotating circular paper disc inside with different images printed on it.Page 4: Titled "Truly Dumb" - the text reads: "As I got to high school, I wondered if I was truly dumb. Teachers would refer to lessons we “should’ve” learned and I couldn’t find the words or the connections. I then developed two masks as a young Filipina growing in Guam’s competitive All Girl Catholic School: humor and hard worker. With these masks, I would be likable to my peers and teachers by choosing to be disarming and loyal. Each math class, I suffered dyscalculia (inability to decipher numbers and their connections) and was shamed by my teacher for my constant failure. Crushed and crying with my remaining sense of effort, my mom yells at me the whole ride to sign me up for tutoring. I didn’t know then she was afraid that I inherited her inability to do math along with my father and brother." There are 3 photos of Jean smiling during her college years. Digital stickers include: orange squiggle, bubble gum pack, and a heart-shaped box.Page 5: Titled: "Diabetes and Hypertension" - text reads: "While I navigated these murky waters of an undiagnosed life, two underlying conditions would creep into my parents’ lives. Diabetes and Hypertension. With a little bit more knowledge now, I realized the stress they lived with in their own masks of hard work and humor: emotional and stress eating and response. As 2 nurses who worked long hours caretaking for others and making sure patients maintained their wellbeing, my parents legitimized their worth by showing up for everyone else but themselves. Their bodies, minds, and relationship suffered in divorce. No longer could they suppress unresolved large feelings that escalated conflict. The stacked issues consumed their lives and debilitated themselves from self managing their emotions. The solution to separate was the safest, possible route." A photo of Jean and her mom smiling at the camera, both wearing glasses. Digital stickers include: blue peace sign, blue and pink yin and yang, and an array of squiggle.Page 6: Titled "Overachieve in Every Area" - text reads: "Much of my adult life swang the way of my parents after many

attempts of trying to kill myself from the later years of high school to college: overachieve in every arena to mask my suffering. My family fell apart for their own safety. Both parents manage their ADHD the best way they know how: never stopping, always abrasive. My brother inherits that narrative with a badge of honor and even though I feel for his own safety and burnout, I come to terms with not being in control of every aspect of their lives." A photo of Jean and her family smiling at the camera. Digital stickers include: floppy disk, sparkle, old-style cell phone, bracelet with chains (happy face, peace symbol, lightning bolt, heart, yin ang yang).Page 7: Titled "Blessing and Curse" - text reads: "It’s not always been so harrowing and sad living with ADHD and taking a non-medicine route. I’ve learned that its a blessing and curse to have a mind with non-stop ideas. I’ve learned that the speed of my energy can be unmatched when I funnel it into a worthy cause for collaboration or hitting the speed bag at the gym. I used to treat rest like a reward and then burn out because I didn’t feel like

I deserved it. I’ve learned to feel so deeply after years of trying to mask that tender part of my big ol soft empathetic heart. I cry for other people’s kids’ accomplishments and women’s basketball games. I raise my voice on bullshit in the structure of an organization. I honor the art practice that desperately calls to be free in my AAPI peers." Photos of Jean include: her wearing a black and white jersey that reads "BOSSLADY 1" at the back, her and her husband smiling at the camera, and her reading some papers with a pencil between her nose and upper lip. Digital stickers include: a Ring Pop, floppy discs, and squiggle lines.Page 8: Titled "Stop Treating Like a Problem" - text reads: "Living with ADHD is a gift and if more people knew the

signs, they would stop treating it like a problem. Things that help me manage my ADHD holistically (they may or may not work for you, borrow or toss accordingly): (1) Having a device free morning to help my brain catch up on the act of waking up peacefully. I would catch something early on the internet that could ruin my day or make me reckless. (2) Doing a bit of a workout in the morning: stretching, yoga, kickboxing or walking. Helps me calm down my static hyperactive self before I head into the workplace. (3) Spacing out my big tasks into little tasks. Allowing brain breaks when I feel overwhelmed, no longer comprehending the task, or lacking in concentration. It helps to relax my brain on something fun and mindless for no longer that 10-15 minutes as a palette cleanse into the task at hand again. (4) Permission for fun and relaxation. Sometimes I’ve trained my hyperfocus into workaholism. So it helps to schedule a whole day for myself, my needs, and wants. (5) Celebrating my wins. I can get really hard on myself for mistakes I make reading numbers, remembering dates, and/or taking on too much. At the end of the day, my efforts make me proud of my personal best and my mistakes remind me how it's okay to be human. My grace to myself is an extension of grace I can offer others. (6) Days that I am able to sleep for an 8hr rem, drink enough water, and eat are wins that my body thanks me for because of the rest and nourishment it deserves for working so hard." Digital stickers include: Rubiks cube, Tamogotchi, stars, dots, and squiggle lines.

Khris Baizen

Khris Baizen (He, Him, His) is a

fully-fed Asian man with horn-rimmed eyeglasses and side parted black hair.

— Event Infrastructure Services— Asian & Pacific Islander ERG Founding Lead – Community & Industry Engagement

Embracing My Journey: Strength Through Adversity and Community

May 2024 — Writing by Khris Baizen

As a disabled and neurodivergent professional and now an Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) community builder, my journey has been anything but straightforward. The path has been riddled with challenges, but it's also been illuminated by the incredible support of those who truly understand and those who have shared similar struggles.Growing up, I constantly felt like an outsider. My hard-of-hearing disability and neurodivergence set me apart in ways that many people around me couldn’t understand. The pressure to fit into societal norms and cultural expectations was immense. Balancing my multi-cultural identity with traditional values that often emphasized conformity over individuality was exhausting (Masking and constant chameleoning of my personality in the pursuit of belonging).School was a battlefield where I fought to be seen and heard. My neurodivergence made it tough to thrive in conventional learning environments, and I often felt sidelined. Attempts to "normalize" my behavior only deepened my sense of isolation. Being labeled as different stung deeply, and the constant struggle to fit into predefined molds was disheartening.When I entered the professional world, these challenges didn’t just disappear—they evolved. The corporate environment, with its unspoken expectations, became yet another place where I had to prove myself. My disabilities aren’t always visible, which led to assumptions and judgments that made navigating my career even more challenging. There were times when I seriously questioned my place in this world, when the weight of my struggles felt almost too heavy to bear.But amidst all this adversity, I found a beacon of hope: community. Connecting with others with similar lived experience was transformative. The Southern California event professional community, in particular, provided a sense of belonging that I had long yearned for. Here, I found people who understood the intersection of my identities, who validated my struggles, and who celebrated my successes, no matter how small they might seem to the outside world.Being part of this supportive network taught me the importance of self-advocacy and resilience. I learned to embrace my disabilities and neurodivergence, not as hindrances, but as integral parts of who I am. The community encouraged me to voice my needs, to seek accommodations, and to stand firm in my worth. They showed me that my unique perspectives were not only valuable but essential in creating a more inclusive and understanding society.My journey is far from over, and I continue to face challenges. However, the strength I draw from my community fuels my determination to keep pushing forward. I am committed to using my experiences to inspire, educate, and empower others. By sharing my story, I hope to break down the barriers of misunderstanding and stigma that so many of us face.To anyone reading this who might be struggling, know that you are not alone. There is power in your story, strength in your journey, and an entire community ready to support you. Embrace your identity, advocate for yourself, and find solace in the connections you make along the way. Together, we can create a world where every individual is valued and included, no matter their background or abilities.

Kim Chua

Kim Chua is a Malaysian-Chinese American woman who self-identifies as having ADHD with a winning battle against depression.

Coursing Through the Haze: Navigating Disability and Neurodivergence as an AANHPI Woman

May 2024 — Writing by Kim Chua

The fog is thick, obscuring the path ahead. For many disabled and neurodivergent individuals within the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) community, this metaphorical fog represents the challenges, misconceptions, and barriers that shroud our true selves. It is a haze woven from the threads of societal expectations, cultural stigmas, and a lack of understanding that often leaves us feeling lost, misunderstood, and disconnected from who we truly are.Yet in the heart of this dense fog, a melody echoes - my own symphony of disability and neurodivergence as an AANHPI woman. The whirlwind of ADHD thoughts swirling, the relentless distractions pulling, the restlessness intertwined with depression's heavy shroud. For years, I trudged through this quagmire of mind, weighed down by the model minority myth and pressures to conform.As a second-generation Malaysian Chinese American, intergenerational trauma and stigma around mental health conditions threw me into torrential turbulence from a young age. The eldest daughter of immigrant parents from Southeast Asia, I found myself the protector, parental figure, and self-made therapist for my family amid domestic violence and chaos.Through the turbulence of my childhood, I masked my undiagnosed ADHD, striving in vain to achieve the mythical "model minority" success that eluded me. Depression seeped in during college, its taunts convincing me I was unworthy and a failure as an Asian American unable to persevere with grace like my high-achieving peers.But I've embarked on a journey of self-discovery, parting the fog in late 2023 to find language articulating how my neurodivergent mind dances to a distinct rhythm. With self-awareness came self-acceptance's warm embrace. I began harnessing my hyperfocus to ignite creativity's flames, celebrating my unconventional thinking as innovation's spark.Depression is no longer a looming shadow, but a chapter forging my grit - navigating its depths, seeking support, finding solace in moments when light pierces through. As a proud disabled neurodivergent AANHPI woman, I refuse to be constrained by narrow "normalcy." I revel in my uniqueness, honoring the singular neurodivergent perspective I contribute.And I am not alone in this journey. A vibrant community treads this path alongside me, offering camaraderie as we unite to challenge the insidious cultural stigmas and "saving face" mentalities that have long plagued our diaspora.For too long, this haze, born of societal biases and lack of understanding, has obscured the vibrant neurodivergent identities within the AANHPI community - leaving many, especially women and elders, feeling adrift and disconnected from their genuine selves.But in our community, we find strength in our diversity. Our disabilities and neurodivergences are not flaws, but integral parts of our identities - shaping profound perspectives and rich lived experiences. Together, we amplify our voices in defiant chorus, shattering stereotypes that have long plagued us. We reject notions of incompatibility with success and boldly challenge narratives perpetuating shame and stigma.As our community's tenacity strengthens, we unlock doors long barred - the door to self-acceptance, embracing our differences; the door to understanding, educating others on our realities while fiercely advocating for inclusion; the door to collective healing, sharing our stories and shedding societal burdens to breathe freely as our genuine selves.Yet our journey does not end there. We must hold these hard-won doors open for those who will follow. We nurture the next generation, fostering future trailblazers. We unite with organizations and policymakers, dismantling systemic obstacles. We create resources and platforms, amplifying the long-silenced voices of our disabled and neurodivergent AANHPI community.Coursing through the haze, we navigate obstacles with newfound clarity and purpose. Guided by our community's collective wisdom, propelled by the knowledge that our disabilities and neurodivergences are wellsprings of enduring strength - not limitations. We leave a trail of empowerment in our wake, inspiring others to reject confining definitions, banded together in creating a world that celebrates disability and neurodiversity where accessibility is the standard.This is a communal journey, marked by our unbreakable strength and determination to unlock and hold doors for all who have felt trapped in the fog. It requires us to embrace our genuine selves, rejecting narratives that have long constrained us, coursing through the haze emboldened and empowered.The challenges that lay ahead are vast, but rendered manageable by the support and understanding within our disabled and neurodivergent AANHPI community. So we unite, boldly proclaiming disability and neurodivergence as beautiful, essential variations of the human experience. We are disabled. We are neurodivergent. We are strong. Rewriting the narrative, one resolute step at a time, parting the fog to reveal the path ahead.

Kristen Higa

Invisible by Disability, but Visible in Community

May 2024 — Writing by Kristin Higa

In the fall of 2011, I was admitted to an emergency room late one evening after surviving a major car accident. Despite breaking the front car window with the top of my head, I was completely coherent upon arrival, able to recall major political figures and speak in complete sentences. The doctor on duty was about to sign my discharge paperwork when a Filipina nurse pleaded with him to give me just 15 more minutes. Shortly thereafter, I fell into a two-day coma. This young nurse's intuition and compassion saved me from severe disability or worse, death.The concept of representation is often discussed in terms of seeing people who look like us in movies, as surgeons, or CEOs. For me, representation means much more. The bravery and kindness shown to me by that nurse in Beverly Hills exemplified true representation. She could see beyond my mannerisms and speech, recognizing what others could not. To me, representation means being truly seen.Growing up Japanese American in Hawai’i, I was taught to 'blend in.' My grandfather, who lived through WWII, escaped internment by proving his allegiance to America. This desire to assimilate was passed down from him to my mother, and then to me. As a result, I didn’t learn or speak Japanese; instead, I studied Latin and Spanish. I didn’t attend the Buddhist temple weekly but went to a Christian church at my private school. Our vacations were not to Japan, but to Europe.Following my traumatic brain injury, I continued to do my best to blend in, despite the permanent cognitive and physical disabilities. I grew my hair long to hide my scars and pretended to smell even though I had lost most of my sense of smell. It wasn’t until I found a job at Asians and Pacific Islanders with Disabilities of California (APIDC) and joined their Youth Leadership Institute that I met others facing similar or worse circumstances. There, I learned how to advocate for myself and others living with disabilities.Now, I am open about my cognitive and visual disabilities, and I am transparent about their impact on my work and friendships. The most challenging aspect of my situation is that my disability is invisible, making errors and mistakes often inexcusable. Whether around colleagues, friends, relatives, or strangers, there is a strong expectation to be 'normal' and to 'fit in,' making acceptance a continual battle.What gives me strength and confidence is knowing that I have overcome far more difficult challenges in the past. Advocacy and standing up for myself not only make things better for me but also for many others. I find strength in our community and love to see others finding empowerment and comfort from it as well.

Lilian Nelson

May 2024 — Writing by Lilian Nelson

Click here to access Lilian's written document where the first letter of each word is bolded for reading accessibility.

What does it mean to be a neurodivergent Asian in a neurotypical world... That's an interesting question because it really depends on what is considered "typical," doesn't it? And due to the model minority myth perpetuated by both Asians and non-Asians alike, the "typical" Asian is often expected to be a socially-conforming perfectionist - quite the opposite of "disabled."I am a Taiwanese American who immigrated to the States as a toddler, now in my mid-30s. I grew up in a household that was dominated by impossible expectations and domestic violence - a theme I hope is becoming less common with each generation. My parents believed the word "disabled" is only a fictional concept reserved for the undisciplined and incapable, while less than perfection invited bruises and wounds that I would have to hide in public.Complex PTSD is a frequent co-morbidity with other forms of neurodivergence, typically as the result of societal responses to those other conditions. Conversely, the very-early onset of Complex PTSD can affect neurological development to resemble/present as another condition. So if you grew up in an environment like me, your childhood trauma may be the very reason why you struggle to meet your parents' expectations... which only invites more childhood trauma.The intersectionality of my disabilities and my Taiwanese culture catalyzed my suffering and loss of identity. I brute-forced my way through (what I now know are) symptoms at the expense of my well-being - physically, mentally and emotionally. I thought to myself often growing up, "I could probably be an actress with how good I'm faking all of this." I abused various vices and experienced severe suicidal tendencies behind a smiling face and successful career through my 20s, and burned out in my 30s. This has given me the greatest gift of recognizing when someone is burying pain or grief beneath the surface, and how to support and love them through this self-denial. I wouldn't give this up for anything - not even a do-over.With time and a lot of help, I learned why I did things such particular ways and how to mitigate the symptoms or use them in my favor. I began openly discussing my needs and limitations in the workplace to hopefully free others still stuck behind a mask. Only then did I experience a very interesting dynamic as a neurodivergent Asian: the model minority expectation has forced many Asians into presenting as overachievers despite any invisible obstacles. At the same time, we may also face neurodivergent folks with internalized ableism who believe if you're able to achieve you must be lying about being disabled. This can result in neurodivergent Asians being rejected by both of their communities.Six months ago, mid-burnout, I sought to deconstruct the unhealthy ideas I absorbed from both worlds to make life easier and more peaceful. While my ADHD symptoms are still constantly on display, I give myself grace and laugh about it rather than beat myself down. I allow myself the freedom to explore interests and hobbies simply for fun and not for performance. My body tells me how much I can handle each day, and I listen instead of hurting myself due to external expectations. I surround myself with people who "get how I am" (most share similar traits, habits and challenges). I reject the pursuit of capitalistic trophies, prioritizing a lifestyle that better suits how my noggin works. Essentially, I've redefined who and what is "typical" in my life as a neurodivergent Asian, and that is how I've found my peace.To decolonize the rigid societal box Asian Americans have been shoved into for generations is to reject toxic perfectionism and blind conformity. It is to embrace all parts of your being as "typical." It is to dismiss the notion that neurodivergent folks must integrate into expiring societal structures, and instead it is to inspire society into integrating new ways of thinking, communicating and being.With love and hope for the future,

LilPS. I really wanted to record this but it's just not happening for me... thank you for reading.

Maddy Ullman

May 2024 — Writing by Maddy Ullman

What a cocktail of life I have as an Chinese American adopted woman with cerebral palsy, diabetes, ADHD and so much more? I’m exhausted but never bored.The intersectionality of adoption and disability has shaped my life in the ways that the universe, God, or whatever else one would believe in could orchestrate. The intersection where all my identities meet is bittersweet. I cannot talk about disability without talking about adoption and vice versa. Sometimes simply existing feels like trying to stuff the whole ocean into a lake and always overflowing. Fighting so hard to be alive. To be seen. To be heard. To not be a burden in an ableist society. Sometimes it brings me to my knees (metaphorically).Being an Asian adoptee with the physical disability means that I will never be enough no matter where I go. Culturally, I will never be Asian enough for Asian people and will never be white enough for white people. I struggled in the small town I grew up in. I struggled feeling like the only Asian person. My classmates loved pulling eyes into slants and proudly proclaiming “I’m Chinese” There was a time where I would have given up anything to have blond hair and blue eyes because that was what I saw.People tell adoptees “You’re so lucky to be adopted” all day every day. Being visibly disabled means this phrase has been ingrained in me by default. I never thought of disability and adoption being fused together to bind my story together. They were two different circumstances in my mind. Until my world shook.My adoption story was supposed to be simple. I was given up and fostered by a Chinese family until I was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at 1 1/2. Stayed in hospital for eight months and then eventually adopted by my family when I was 3 ½. The name on my passport has stayed the same for twenty-seven years and counting. In 2016, I officially decided I wanted to search for the birth family. My mother sat me down and told me the truth. The foster family was my first adoptive family, and I was given up because I was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. My parents were told to never tell me. If I never searched, I would have never known.Adoption is tragic. Adoption can be beautiful but at great cost. Adoption exists because of loss. On that day, I realized that I was adopted into my culture and rejected because of my disability. I was abandoned again because of circumstances I couldn’t control. Because of who I am. Because of the body I inhabit. What a punch to the gut am I right? In my journey, the intersectionality of adoption and disability Is full of grief. I have contemplated my existence. My purpose. My worth as a human being. Sometimes I can't believe I'm here. I may not have had anyone to look up to when I was a child but I'm here for the next generation.What does it mean to be a Chinese disabled adoptee? For me, it means that life is never boring. Disability is hard. Adoption is hard. Like trying to move a boulder up a mountain every damn day. Guess what gives me hope? I'm the writer of my own story. All of these circumstances all of my identities, all of my struggles are all things I can use to my advantage. I'm my biggest cheerleader. Because of everything in my life I can connect to so many people. Disability has taught me to be adaptive to problem solve, even though the whole world needs more accessibility. I can manage. My whole life changed when I decided that I was enough. I hold on to that and use my talents for good. Surround yourself with people that believe in you. People who see you. Community is so powerful. No matter who you are. no matter where you are. No matter what circumstance. You are the one who gets to define your life.

Martin Tran

Book Display

May 2024 — Photo & Book Display by Martin Tran

Inside a book store, Martin, a Vietnamese American man with black hair, wearing glasses, a blue jacket, black shirt, gray pants, and white shoes, smiles in front of a book display with an array of Asian American authors.

My name is Martin Tran, I am Vietnamese American and I am avid reader and my career path is bookselling/ Library services. I am a child of Vietnamese immigrants. I graduated from San Jose State with a B.A in Creative Arts and an A.A in English at Evergreen Valley College.I have a developmental disability in speech and language and lazy eye.Last year was my first time creating a book display to celebrate Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month. I wanted to showcase books written by Asian American authors who have been successful in publishing and writing about various topics such as autism being represented in Helen Hoang’s "The Bride Test" and gender in Melinda Lo’s book.

Nathan Chung

Nathan Chung is an Asian male with Autism, ADHD, and CPTSD.

Neurodivergent Asian American

May 2024 — Writing by Nathan Chung

My name is Nathan Chung. I am a Chinese American man who grew up in Honolulu, Hawai’i and now living in Austin, Texas. I am an Autistic person with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), and Complex PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Here is my story.Hawai’i

In the year 1900, my ancestors immigrated to Hawai’i from Guangdong province in Southern China. They were among the 46,000 Chinese people who made the dangerous journey in the late nineteenth century looking for new opportunities. I was born the youngest in a family of all boys, but there was a problem. After giving birth to four boys over several years, my mother did not want any more kids. So, I was seen as a burden and unwanted. To make matters worse, my mother was in her 40s when she gave birth to me, which increased the chances of me having Autism by 50% according to science. My mom would often call me “dumb thing”, “good for nothing”, and “pilau”. In Hawai’i, “pilau” is a pidgin word used by the local people to describe something that is dirty or filthy. So, to my mom, I was filth and not wanted. On occasion, my mother would even tell me to kill myself so she could stop taking care of me.From the beginning I knew that I was different. In school, I would always be running off and exploring, not listening, not interested in making friends, daydreaming, and I was just labeled weird to people. Even my brothers would torture me by reminding me how broken I was because the teachers complained about me not listening and just being hardheaded. By nature, people are uncomfortable around people who are different. I did not get along with anyone growing up. Being Asian made things more difficult since I brought shame.Good Son

In many Asian families, the expectations are high for children to serve their families, and this often follows the common gender stereotypes. Similar to Disney’s Mulan, daughters are expected to have children, especially boys. Sons are expected to be successful, marry a good woman, and build a family. I remember my maternal grandmother very much desired for her sons and grandsons to find high-paying and prestigious jobs such as being a doctor or a lawyer. For me, I was not interested in those, I wanted to work in IT and with computers.This resulted in me being seen as a deviant in my family, I was going rogue. Being different, strange, or crazy is still seen as shameful in Asian families. Concepts such as honor and saving face put up a cultural wall where mental health is often not discussed and more often than not, not addressed at all. It is

easier for people like me with mental health issues to be written off as stupid and not important in families, even today. So many people like me suffered in silence and often ignored.Still, I was programmed at an early age that I had to be a good son. Thousands of years of Confucian thought demanded filial piety. So, I met a lady on eHarmony, got married, bought a house, and started to build a family in California. I was doing what my parents expected of me by being a good son. I just had to surrender my wants and needs and ignore the fact that I was different by hiding parts of my

personality that was not acceptable. In the world of Neurodiversity, this is called masking.The Top

Eventually, I got a job as a consultant at EY, one of the Big 4 firms. That meant working with customers to do projects and I was extremely excited. I got to work at a big-name company, travel all around the US, I ate some of the best food in the world at Michelin Star restaurants, and I was happy at work for the first time in my career. My work was recognized, and I won awards. I was at the top of my game, but then tragedy struck.One day my boss, Paul, suddenly took his own life. He was the best boss I ever had. He helped to hire me and support me. Good bosses are hard to come by, so the news of his death was shocking and devastating to me. It was like taking a hammer and shattering a mirror and seeing my career in pieces.

My world literally came apart. There were days I could not sleep, I would be on the ground shaking from anxiety, and my work suffered. My wife left me and we got divorced. I needed help.This led me to enter an emergency mental health support program to address my anxiety and depression. The support group would meet weekly to talk about issues and feelings. It helped to stabilize my mental health after a few months, then I left. But I still felt the need to take the next step in my journey to understand what was going on under the hood.Diagnosis

I knew I was not normal, and something was going on with my mental health. It felt like I was investigating a crime scene. There were evidence and clues throughout my life, but I was not able to solve the case. This led me to read a lot of books and search the Internet about mental health. One book that was a breakthrough for me was “You Mean I’m Not Lazy, Stupid or Crazy?” by Kate Kelly and Peggy Ramundo. The book is a bestseller about ADHD and after reading it, I felt like the pieces were coming together and my crazy chaotic life started to make sense, it was clear that I had ADHD. After reading other books, it became apparent that I have Autism as well. Case closed right? But this was not enough for me. Like a medical case, it was undeniable I had symptoms of Autism and ADHD, but without a

diagnosis, it was still speculation.I was living in the San Francisco Bay Area of California at the time and began to look for a mental health professional who could test and assess me for Autism and ADHD. To my frustration, I could not find one in California who works with adults since Autism is commonly associated with children. It was another wall blocking my progress. Then I moved to Colorado for work and to my surprise I did find someone who could work with me. I was shocked that insurance did not cover diagnostic testing and would cost several thousand dollars, but I still decided to proceed anyway because I had to know the truth. The result? In January 2021, I was formally diagnosed by a psychologist with both Autism and ADHD.I felt relief and a sense of peace. The crime and mystery had been solved. I could finally move forward with my life.Civil War

Getting a diagnosis would be the end of the story for many people, but for me, the next step was to fight myself. I grew up struggling to fit in and wanting to be normal. Since we live in a world where being different is demonized and shamed, my mind struggled to accept that I have a disability. It felt like having a civil war going on. Part of me wanted to be normal and fit into the world, but the other part of me was a rebel who knew I did not fit in and was fighting for acceptance. Getting a formal diagnosis forced me to accept the harsh truth that I have a disability and that I was different, the rebel had won.It felt like a change in government, this meant that I had to make life changes to adjust. This included changing my mindset, getting my chaotic life organized, and learning to do things better. It was like being blind most of my life and finally being able to see. Acceptance of my disability meant a new life and world for me, but this still was not enough. I wanted to do more.Advocacy

I wanted to help people so I started volunteering and doing advocacy work around Neurodiversity, disability rights, and mental health. Women in particular need help, since the stereotypes in Neurodiversity suggest that only males can have those conditions, not females. This led me to WiCyS (Women in Cybersecurity), the largest nonprofit in the US that advocates for the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in cybersecurity. Since I worked in cybersecurity, I figured that WiCyS would be a great place to help. So, I reached out to their leaders, and it turns out they wanted to build out a Neurodiversity special interest group and I volunteered and became its leader.Over time, the group became a success, and hundreds of women signed up for the group to learn about Neurodiversity, working in cybersecurity, get mental health support, and get inspired hearing stories from amazing Neurodivergent women. This was very powerful since it is the only group in the world that I know of that supports Neurodivergent women in cybersecurity. Eventually, I decided to take things to

the next level and recruited a diverse group of women to form a new board to lead the group and to create a brand new WiCyS affiliate called WiCyS Neurodiversity. After that, I stepped aside as leader and let the women on the board lead. The group was amazing, and it won an award in 2023 for being the top WiCyS affiliate in the world. I felt proud having created a group to help others.Besides WiCyS, my advocacy work expanded into other areas. I created a podcast called NeuroSec, where I interviewed guests about Neurodiversity and cybersecurity, and it did so well that it was on the list of the top 10 podcasts in Japan for a week in 2021. I created a newsletter also called NeuroSec where I wrote about my life as a Neurodivergent person working in cybersecurity.Eventually, this led to me speaking about Neurodiversity at many conferences and events. This included talks at the SANS Institute, Microsoft, Uniting Women in Cyber, GRIMMCon, and two United Nations agencies. I felt that it was important for me to share my story and for people to see someone like me who is Neurodivergent and not be afraid to be themselves. For my efforts, I won three awards.Reflection

Does this story have a happy ending? No, it does not. There are days when I can be energetic and get through the day. On other days, I am overcome by the darkness and fall into depression. I take things one day at a time. I am openly Neurodivergent, I am not ashamed of who I am, and I no longer hide my disabilities. I am what I am. I am a Neurodivergent Asian American.

Niko Galindez

Niko Galindez (she/ her) is a Filipino cisgender woman, bisexual, ADHD, and Type 2 Diabetes. In the photo above, she is seen as a rotund Filipino woman with glasses holding a microphone with an optimistic expression.

Page 38 of "Hear See Here Zine 2024"

May 2024 — Artwork by Niko Galindez

The page is decorated with an array of colors (blue, red, green, and yellow) circling around the Philippines flag. On the left is a vertical pink row of black cats (from ears to nose only). There are various blocks of text. In blue: KA‧RA‧GA‧TAN; alt: OCEAN DAGAT. In red: DUGO BLOOD. In black: Pusa kitty kit kat mewo ~ hey kitty girl ~; Have I become so pessimistic or negative that I have ... I must write something bad with the good? Yes, we're hospitable. We've been scammed by every one who CLAIMS to "HELP" us. We're RESILIENT, we've been F***ED OVER by every one who claims that they're "above" us. I AM traumatized and I have crippling spicy brain!! neurodevelopment disorders. Google It. I (was) am?? Baptized cat‧to‧li‧co; @niko.fka.tabachoy APR 2024!!

Click here to access Niko's page of the zine as a PDF.Niko's page is page 38 of the "Here Seen Hear Zine" Las Vegas Asian American and Pacific Islander Storytelling ZIne 2024. It is supported by University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) College of Liberal Arts & UNLV Asian and Asian American Studies — Click here to view the full zine.

Pam Maranan Parker

Pam Maranan Parker (she/ her) is a

Filipino-American with Bipolar 1 Disorder.

May 2024 — Art by Pam Maranan Parker

IMAGE DESCRIPTIONS

Page 1: Her artwork is abstract with various colors of gold, pin, orange, yellow, and black. There are blue and white butterflies, a gold frame with a human heart at the center, lightning bolts, sea waves, and gold Comedy and Tragedy masks.Page 2: On the backdrop of this collage is a variety of images: wooden rules, clock, array of pills, gears, weighing scale, and grids. Atop are texts in a variety of fonts, the text reads: ways to find stability with bipolar, go to therapy, comply with your meds, be kind to yourself, find your life balance, take it one day at a time.Page 3: The backdrop is the same as Page 2. The text on top reads: Ways to Find Stability with Bipolar, no drugs, limit or even avoid alcohol, get enough sleep, maintain a healthy work-life balance, surround yourself with supportive people, find your life balance

Rachel Cometa Estuar

Finding My Tribe: A Neurodivergent AANHPI Woman's Journey

May 2024 — Writing by Rachel Cometa Estuar

I'm Rachel Cometa Estuar, a Filipina American intersectional woman living on the ancestral lands of the Gabrieleno tribe in Whittier, California. I'm married with two adult sons, and my career has focused on advocating for marginalized communities in the U.S. This includes survivors of violence, under-served youth, the unhoused, and BIPOC neurodivergent individuals, people with disabilities and mental health conditions. I've worked in the fields of public interest law, public health, education, non-profit, and government.Challenges and Realities

Battling cancer three times within a span of 10 years forced me to postpone my dream of completing my Masters degree. This challenging period was the first time I became acutely aware of how disabilities, especially the stigma and biases some people carried, can limit earning potential. Despite having years of successful experience building partnerships with key stakeholders, advocating for change, and developing impactful programs, I struggled to find full time employment. I was feeling that people doubted me; but the worst part was that I doubted myself, too.In 2021, I was invited to speak during AANHPI Heritage Month at an online Clubhouse program. There, I discovered chat rooms where neurodivergent people openly shared their personal stories and struggles they faced at work and with loved ones. It was a space of authenticity, courage, and shared humanity.Not long after, while I was doing research to find best practices for improving the quality of services for people with disabilities looking for work, I started connecting the dots. The symptoms sounded familiar. Then came a medical assessment confirming I have ADHD. It helped explain a lot of things and it was the beginning of my journey of discovery.Then just a few months later, I took a position as Director of Services at a nonprofit organization. The organization advertised disability advocacy as one of its services, so I assumed they would be understanding and supportive of my neurodivergence. Unfortunately, this turned out not to be the case. When I requested reasonable accommodations, my employer denied them. I was shocked and disappointed to find myself becoming part of the very statistics I'd hoped to help address.Hope and a Growing Movement

I share my story because others considering disclosing a disability to an employer deserve a full picture. Discrimination can happen even in workplaces that should uphold disability rights, diversity, equity and inclusion. Sadly, people and places that say they are "person-centered" often have low levels of patience to improve the skills of people with disabilities so that they can succeed. You have to ask, do they believe in the principle of "nothing about us, without us"?But there's a bright side! There are campaigns like a #BillionStrong! which is celebrating the fact that there are about a billion people in the world who are disabled. Together, we can create a future that is more neuro-inclusive, honors the dignity of others, understanding and accessible for all. Public figures are stepping forward to challenge stigmas, and more people are recognizing the toll of "masking" neurodivergence. The more we share our stories and talents, the faster we can change narratives and showcase the positive impact we have and can continue to make.Finding My Neurodivergent Community & My Voice

Finding creative ways to collaborate with my neurodivergent community on social media has been a game-changer. Spaces like LinkedIn, The Mighty, and Clubhouse are where I connect with hundreds of others sharing experiences, resources, and research on neurodiversity. My network of social justice and disability empowerment advocates have become my friends. Together, we are discovering and doing things with local and global organizations like the UN, the Institute of Neurodiversity, Fish in a Tree and the Center for Purposeful Leadership. One of our projects was to produce a short video representing the voices from North America and the Caribbean for the 2024 UN World Autism Awareness Day.Finding my tribe allowed me to rise above the trials and to leave behind toxic people and places. By doing so, I have reclaimed my freedom to reduce stressors and my agency to focus on the parts of my self-care that I neglected. As part of my professional development, I now volunteer with the National Institute of Health to review grant applications. As a woman of faith, I feed my soul by serving in some capacity to bring unity, reconciliation and support to historically segregated (othered) BIPOC communities. As a first-gen Filipina American immigrant, I have learned a lot through my adversities. The hardest lesson came after my disclosure but I am grateful that "I got to the other side of my adversities with some help from a community of neurodivergent friends and allies!"

Sarina Tran-Herman

May 2024 — Video by Sarina Tran-Herman

Transcript